Who this post is for: Anybody who needs to write an essay about a quote; anybody applying to Colgate or Penn.

Note: some of the links in this post are samples of full length posts available to my clients and subscribers. Subscriptions require that you create a WordPress account and pay me a small fee, or that you retain me for editing or college app services. See the “About” section for more information.

An increasing number of universities are timing their own release of supplemental prompts to coincide with the Common App rollout. The Common App posts a “draft” form by early summer, but the website for the Common App is taken down in mid to late July and then goes live on August 1st; this year, the site goes offline on Friday, July 13, at 11:59 PM. I have the common app prompts available on this post: The Common Application for 2012.

Colgate and Penn are among the few universities that have already posted their 2012-2013 supplemental prompts, so let’s take a look at their offerings. I will follow some analysis of each prompt with a discussion of approaches to each prompt.

Colgate’s prompt asks for what I would call a fictional travel essay. Here it is:

At Colgate we value global awareness and the diverse perspectives of our students. Through travel, students are able to experience different cultures and take advantage of new opportunities that can make our community richer when they return to campus. If you had the opportunity to travel anywhere in the world during your time at Colgate, where would you go and why?

This prompt is an alternate to the classic “My Trip” essay, in which generations of high school students have bored readers by summarizing a trip to a foreign place and describing the odd habits they encountered there. It is possible to write an interesting essay about a trip, as hundreds of books on travel show, but more often than not students generate not particularly interesting descriptions or end up appearing arrogant in their descriptions of foreign places and people.

Colgate’s prompt is an attempt to avoid the typical “My Trip” essay by having you invent a destination. This means that they are trying to evoke your imaginative abilities as much as your cosmopolitanism, so you should avoid simply describing some place that you have already been. An exception to this might be if you have a commitment (in a Peace Corps kind of way) to a foreign country, and you intend to continue it. I have had clients who have gone on missions or service trips to do everything from constructing housing and water facilities to assisting with medical services; if you’ve done something along these lines and you are committed to doing it again, then you might want to write about this place–but keep in mind that Colgate asks you to imagine a future trip, so make clear an abiding commitment which you intend to deepen during your time at Colgate. Also make clear what it will allow you to bring back to the Colgate community and what new things you might learn or do. It might help if this relates in some way to your major.

In addressing this Colgate prompt, you need to consider what your audience is looking for–if you are a first-time visitor to this blog, you should look at some of my earlier posts, like this one: Evading the Cliche. Colgate telegraphs the values they seek throughout the prompt: we value global awareness and . . . diverse perspectives . . . Through travel, students are able to experience different cultures and take advantage of new opportunities that can make our community richer when they return to campus.

In addressing the ideals established here by Colgate, try to avoid simplistic, Social Justice class responses. I don’t have a beef with the Social Justice curriculum as an idea, but increasingly I am seeing a kind of social justice cliche, or set of cliches, in response to prompts about international problems and in response to prompts which, like this one, are motivated by the university’s desire to create more aware and cosmopolitan people. I call this the reverse of the cultural superiority fallacy, which I will discuss in a moment. Before I do, please see my earlier post here, where I address some of the cliched responses elicited by problem essays, cliches which this prompt may also elicit.

Keep in mind also that this Colgate essay prompt is aimed at a communitarian as well as cosmopolitan ideal–whatever you learn will bring something back to the Colgate community and so, I guess, help Colgate deepen the cosmopolitanism of America at large. You are the point of the essay not as an isolated individual but as part of a learning community.

A major risk of writing a travel essay, even a fictional one, is the cultural outlook we all carry. It’s almost impossible to avoid viewing and describing other places and cultures from the point of view of your own, and many well-intentioned travelers past and present come across as patronizing or arrogant in describing the places they visit and the people they see there. I would say that this risk is not mitigated by the fact that Colgate asks you to invent a trip. If you haven’t been to the place at all, it is nearly certain that all of your information is second-hand and without adequate context. So be wary of passing judgements, especially about people and places you have not experienced or not experienced in depth . . . and even if you have, try to be aware of your own assumptions and how they shape what you say. Try starting here for a serious examination of this problem: ethnocentrism. Keep in mind the fact that Romanticizing a place or a people is nearly as ignorant as being dismissive and can be just as patronizing.

You could make stereotypes and cultural myopia the explicit topic of your essay by writing about a place that many have preconceptions about. Pick an easy target, like the French . . . it wasn’t so long ago that some Americans took to eating something called Freedom Fries instead of french fries . . . and more than a few Americans are intimidated by the mere idea of trying to order from the archetypal Arrogant French Waiter. The archetypal Arrogant French Waiter does exist, of course, but he’s just as easily found in New York or San Francisco as he is in Paris, and he may not even speak French.

It will help this essay if you have a fascination with some aspect of another country or culture–maybe you are into Anime in a deep way, or maybe you are really into some form of dance, like Flamenco. Why not go to the source–or do some research and make a plan to go there? This would definitely help you avoid sounding like a condescending twit-as long as you aren’t faking your interest. For more general comments on the risk I describe above, along with some other things to avoid, see my post from last year: College Essay No-No’s.

If you are in an international school that follows an International Baccalaureate curriculum, I suggest that you consider some of what you have learned in your Theory of Knowledge class and essay. The cosmopolitan philosophy of IB fits this prompt; how might a trip develop what you already know about different ways of knowing? The IB philosophy matches up well with the ethos expressed by Colgate in this prompt.

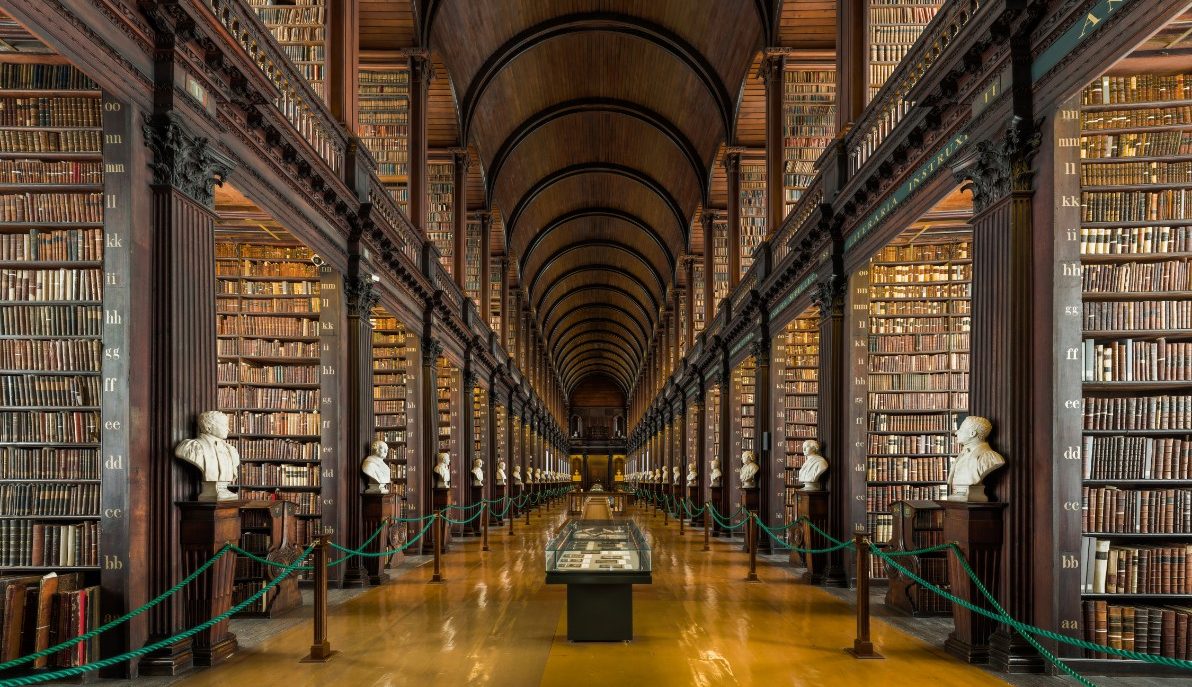

If you are daring and creative, you might write a true work of fiction, even write about a place that does not exist but which is in some way an analogue if not an allegory for some aspects of the modern world. In this case, you could take a cue from Jorge Luis Borges, who is often called one of the world’s great short story writers, though it might be more accurate to call him a writer of fictional essays and memoirs. Borges creates places that never existed but might have, labyrinthine libraries that sprawl endlessly across some parallel universe, fragmentary detective stories set in vaguely familiar lands that have never existed, encyclopedias of things that might be . . . Borges spun out fantastical and science fictional tales and treatises that always say something about the here and now. Check him out in that Borgesian realm, the internet: a good Borges website.

And finally, keep in mind this: nobody is going to check that you follow through on any commitments you might make in this essay, though it would help your essay if you felt committed while you were writing it.

Next up are Penn’s prompts for this year:

Penn

Short Answer:

A Penn education provides a liberal arts and sciences foundation across multiple disciplines with a practical emphasis in one of four undergraduate schools: the College of Arts and Sciences, the School of Engineering and Applied Science, the School of Nursing, or the Wharton School.

Given the undergraduate school to which you are applying, please discuss how you will engage academically at Penn.

(Please answer in 300 words or less.)

Essay:

Ben Franklin once said, “All mankind is divided into three classes: those that are immovable, those that are movable, and those that move.”

Which are you?

(Please answer in 300-500 words.)

I am not going to do an analysis of the short answer prompt as it is specific to the different schools and majors offered by Penn. You’ll want to spend some time thinking about the major you intend to choose, and if you don’t have one, start researching before responding to this prompt. The Penn website is a good place to start.

Let’s have a look at the Ben Franklin prompt. The first thing I will point out is the obvious–this is an essay about a quote, and as with most of this class of essays, there is little in the way of background for the quote, particularly since, in this case, the quote is an aphorism-by definition, an aphorism should distill wisdom, not provide an explanation of how it was reached. I discussed writing an essay about a quote in several posts last year, so you might want to take a detour to explore some of that before moving on to my specific discussion of Ben–try this link on last year’s Princeton prompt, among others: Writing an Essay About a Quote.

Penn could have used a more obscure source for their aphorism; the fact that they chose one identified with Ben Franklin is suggestive. To me what it suggests is politics. Whatever you do with this quote, knowing something about Franklin himself is helpful, and about his times– Ben Franklin was a scientist, a printer, a successful small businessman, a lady’s man, a drinker and gourmand, a Founding Father of the United States as well as our most important early diplomat . . . and therefore a politician, a word which seems to have become dirty of late. Perhaps this has something to do with Penn’s use of this aphorism, as it can be read as a fundamentally political observation. Franklin himself was also a master of the art of compromise, repeatedly assessing and persuading assemblies and individuals at home and abroad.

Franklin’s aphorism offers a way to classify and divide any group, but it is also very open to interpretation, and how you interpret it will say a lot to your application reader. I mean by this that you have to assign values to the categories Franklin establishes–it’s hard to create a classification system for human beings that does not also create a hierarchy, and in creating hierarchies, you are at risk of seeming self-righteous or narrow-minded or naive.

One example of how to use Franklin’s triptych might be to argue that, in any given group, you have people who are inflexible, even fanatical, people you might call The Immovable; then there are people who are compromisers, whom you might call the movable, and finally there are those few people who move, the leaders. If you examine the U. S. Congress using these types, you might find that politicians who claim principle may not look so good in contrast to those who are willing to compromise. If you set it up this way, you obviously would want to be one of the leaders, those who move, though you would praise the movable for being practical.

On the other hand, if you went in this topical direction, you would want to keep in mind the danger of oversimplifying the nature of politics and conflict–when real and important issues are at stake, compromising may actually be surrender of important principles. I think that one way to read the current political impasse in the United States is to see it as a real conflict over real ideals, both practical and theoretical. When faced with fanatics or ideologues, even compromisers may become immovable in response. Perhaps those who otherwise might be movable become immovable when facing radicals or fanatics, and so save the Republic . . . after a long and ugly political fight.

As you can see, answering the question “Which type are you” depends completely on how you define the terms, what qualities you assign to them. Maybe Franklin’s three types are just a description of people who are more or less peripetetic, or more or less inclined to changing channels on the television. I’m sure you could have some good, satirical fun with this one, but use caution, as always, when relying on humor in an app essay.

You need to think about this one, and you might ponder deeply what your audience, the Admissions Officers, are after in asking you this question in this most political of years.

I also suggest that a little research and reading may lead you to a good idea for this essay, or may help you develop a good idea into a powerful essay. One way to do this would be to read one of the good biographies of Ben Franklain.

Another way is to find other philosophes like Ben–Franklin’s aphorism is of a kind with the tactical and political aphorisms of many great thinkers–Macchiavelli, for example, or Sun Tzu, the great Chinese strategist who said that in any conflict you must first know and understand yourself and then know and understand your opponent–which might also be a way to look at the meaning of what Franklin says. See this site on Sun Tzu’s Art of War or find a good print translation, looking for one with an introduction that puts Sun Tzu and his work in meaningful context, such as this one by Thomas Cleary. For some advice from Machiavelli, try this site: excerpt of Machiavelli’s Art of War.

In keeping with this analogous approach, you could write an essay focused on “dueling aphorisms.” This could be either a serious way to explore what Franklin meant by looking at other words of wisdom, or as a humorous exercise in contrasting. Get your hands on a copy of Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations in the reference section of a library, or look here for the 1919 edition online. At the least you can amuse yourself by finding quotations that contradict with Ben’s, or that can be combined with it to go somewhere interesting.

My closing advice is this: Necessity is the mother of all invention and imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Just don’t plagiarize.