Back in the old days, say in the year 2005, the only worry you really had when applying to college in California was whether or not you would get in. Now, not only is it harder to get into college, you also have to worry about how politics (and the economy) are impacting the universities to which you want to apply. Most of the problems you will face, from finding a school to paying the ever-increasing tuition to getting into the more and more crowded classes have a common cause: funding. And funding is a function of political priorities as much as it is a result of economic swings.

Bear with me while I explain, and then I will offer a simple strategic proposal after I outline the current situation.

We could start with the fact that Cal State students launched a hunger strike earlier this month in response to tuition increases and cuts in courses and enrollment. Their solution is focused on administrative pay, which is a satisfying target, but won’t solve the problem. The problem is much bigger.

In March, the Cal State system announced that it is planning to cut up to 3,000 staff members for the 2012-2013 academic year, as well as slashing enrollment–this seems assured if the tax initiatives on the ballot for November, 2012, do not pass. Even if the initiatives do pass, Cal State schools will not be accepting transfers next Spring, meaning the twenty-five or so thousand community college students who are ready to move on to a CSU will have to wait half a year. This means that the current best-case scenario amounts to a freeze in enrollment while services are cut.

If this outrages you, put it into perspective: the system has experienced increasingly severe cuts for the last decade, and at this point it has the same amount of money as it did in 1997, but it has 90,000 more students to serve. Decades of cuts have accelerated in the last four years, and something has to give, so plan not only on paying more tuition per term at a CSU, plan also on spending more time in school because you can’t get the classes you need to graduate.

More time in school means spending more money, so factor an extra term or two in as an additional cost when you set up your application list.

Moving on to the University of California system, the regents are proposing a 6% tuition increase for this fall–this is on top of the increases already planned and implemented–and this increase is almost certain since the U.C. regents say it is based on whether or not funding will be increased for 2012-2013 (hint: it almost certainly won’t be.) This will put the total tuition for 2012-2013 at 12,923, plus other fees. As a result, students attending a U.C. this fall can expect to pay about twice what a student paid in 2007. Worse yet, if the tax measure on the ballot for November fails to pass, U.C. regents will meet to “consider” an additional double-digit increase effective for the next term. Yes, at least 10% will be added on to the planned 6% in the same academic year. The sky is indeed cracked and it will start falling in 2012 if more revenue is not generated.

The focus of rage at this point is misguided but understandable–the hunger strikers I referenced above are upset about administrative salaries, and I agree that it is unfair for admins to get raises while students are hit in the wallet, but saving even tens of millions dollars by freezing or cutting admin pay is the proverbial drop in the bucket relative to cuts of at least 750 million dollars for U.C. and Cal State for this year alone. It might help a little to cut admin pay, and I don’t think any administrator anywhere should be getting a raise when profs and students are taking a beating, but it’s a symbolic act to cut admin pay, not a solution.

Keep in mind that increased tuition accompanied by fewer class offerings are not the only effects of budget cuts. Instructors are increasingly hired as adjuncts and lecturers, which means you increasingly have part-time teachers who are paid less and don’t get the benefits of full-time professors and who teach larger and larger classes. Everything from research to maintaining quality of instruction is compromised as the system cuts costs.

Meanwhile, understanding what is going on is more difficult due to the economic troubles of an entirely different industry–journalism. Local reporting is mixed in its quality, with ABC 7 in L.A., for example, putting out reports like this one, in which the reporter writes about how the U.C. system still has “pricey” constructions projects going “gangbusters.” The reporter finally explains that these projects were funded through bonds, often seven or more years ago, but the headline and focus of articles like this one–which doesn’t really explain anything until the article is halfway through–creates confusion about what the real problems are. Construction which is currently underway has nothing to do with the budget crisis we have right now, but it’s hard to tell that if you are scanning articles like this one.

And the problem is clear, if you step back a bit: the collapse of the housing bubble and deep recession of the last four years have not so much caused university funding to collapse as they have revealed the deep structural problems in education funding in California, problems which go back to the year 1978 and Proposition 13. And speaking of going back to future, Jerry Brown was governor when Prop 13 passed, and while he opposed it strenuously and publicly, he also bowed to the will of the people and implemented it to the letter after it passed.

Governor Brown is nothing if not forthright, and just as he did in 1978, he is presenting the citizens of the state with a clear alternative: vote in November to raise taxes or the budget will be cut even more severely. If you understand state budgets, you know this means big cuts for next Spring, but even bigger cuts for the fall of 2013. And I mean the kinds of cuts that are causing me to tell my college advising clients who live in California to apply to multiple universities outside of California.

And I am going further than that: I am telling my clients who are planning to go to college in the fall of 2013 that, if the ballot initiatives fail in November 2012, they should plan on going to college out-of-state and even outside of the United States. Going out of state or out of the country can be close to the cost of going to school in California now, and in many places outside of the (formerly) Golden State, students will be more easily able to get the classes they need and so to graduate on schedule, which also saves money.

With current U.C. increases planned to push tuition above 18,000 dollars over the next four years, and with the potential for that to increase to over 20,ooo dollars a year by 2017 if the tax initatives fail, going out of state is looking like a good bet to be on par in tuition and expenses or an even cheaper alternative, if you search widely and well.

As an example, out of state tuition at the University of Oregon is currently in the 25,000 range for out-of-state students, but cost of living is lower than at many U.C. schools, and if the November tax initiative fails, tuition in California will race to catch up or pass out-of-state tuition in many states, including Oregon. Oregon has its own severe budget problems, but they do not currently have the catastrophic potential of those in California, and with U of O looking at an endowment and other strategies to boost funding, along with tuition breaks at smaller schools like Southern and Western Oregon, I expect costs in Oregon to be significantly more stable and potentially cheaper than in-state California tuition by 2018, and if you go to a WUE school, it could be cheaper within a year or two. Add to that the fact that U of O is seeking more out-of-state students, and you also have a comparative advantage in being admitted in the first place.

Before moving on, I want to reinforce that Oregon and Washington have serious budget problems and face continuing increases in tuition, which is why you should be looking internationally as well, but relative to California, Oregon and Washington schools are becoming more attractive. See this report for a breakdown of what is happening in the sunny west.

So that’s the takeaway: if you live in California, apply to universities in at least two or three states, and you should also be looking at universities beyond U.S. borders. In fact, nobody should be applying only to California or even solely to West Coast universities. But don’t assume that leaving California means everything will be hunky-dory. Do your homework in assessing the budgets for all universities in all states in which you plan to apply. Most places are suffering. It’s just far worse in California than anywhere else.

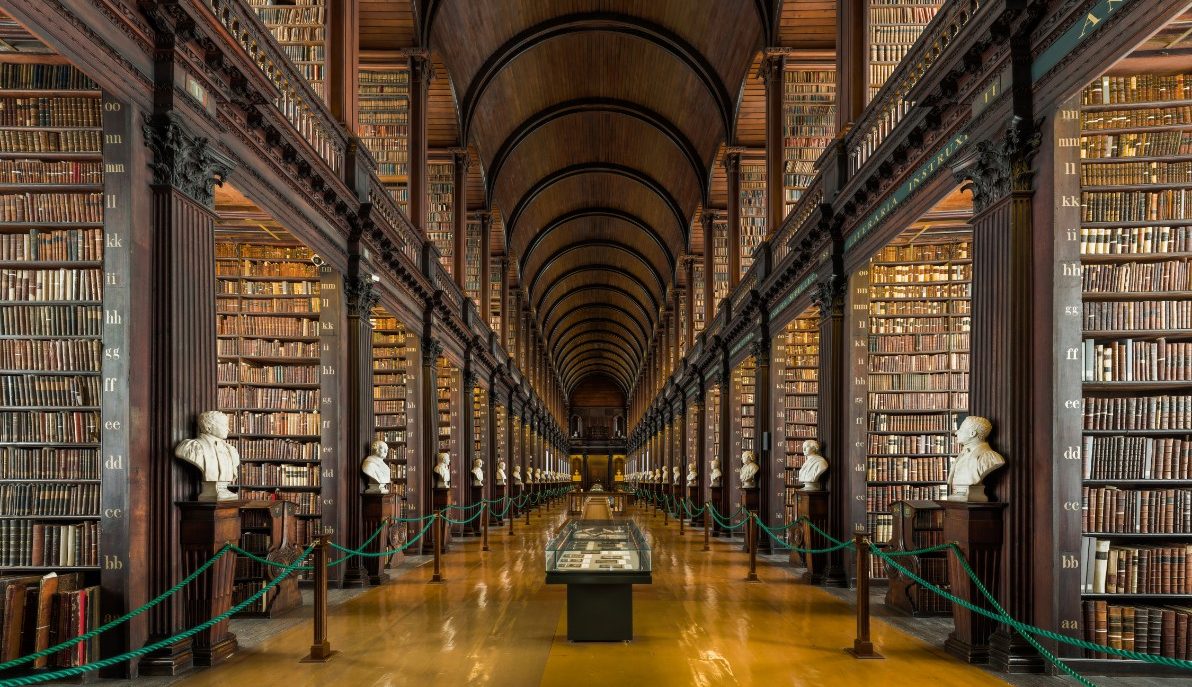

In the near future, I will be writing in more detail about the situation outside of California and outside of the United States, with analysis on specific schools in Oregon, Washington, Arizona, Canada and Great Britain as well as Ireland, but this content will only be available in full to my subscribers and clients.

Good luck and Godspeed in researching colleges, and be sure to look up budget matters–or hire me to help you with that.