Back in Blue (and Red): The U Penn prompts are out. Of all the Ivy League applications, UPenn has the most elaborate contextualizing, and their prompts explicitly demand a level of research and personal introspection that is unique, even in the Ivy League.

Yes, Cornell asks you to explore your major and puts up an annotated list for you to study and then do research from, (please note the date and look for this year’s update on these Cornell prompts) and other schools throw up quotes and context that you really should research (Princeton, Harvard, Yale) but Dean Furda, at Penn, has always done more–and asked for more.

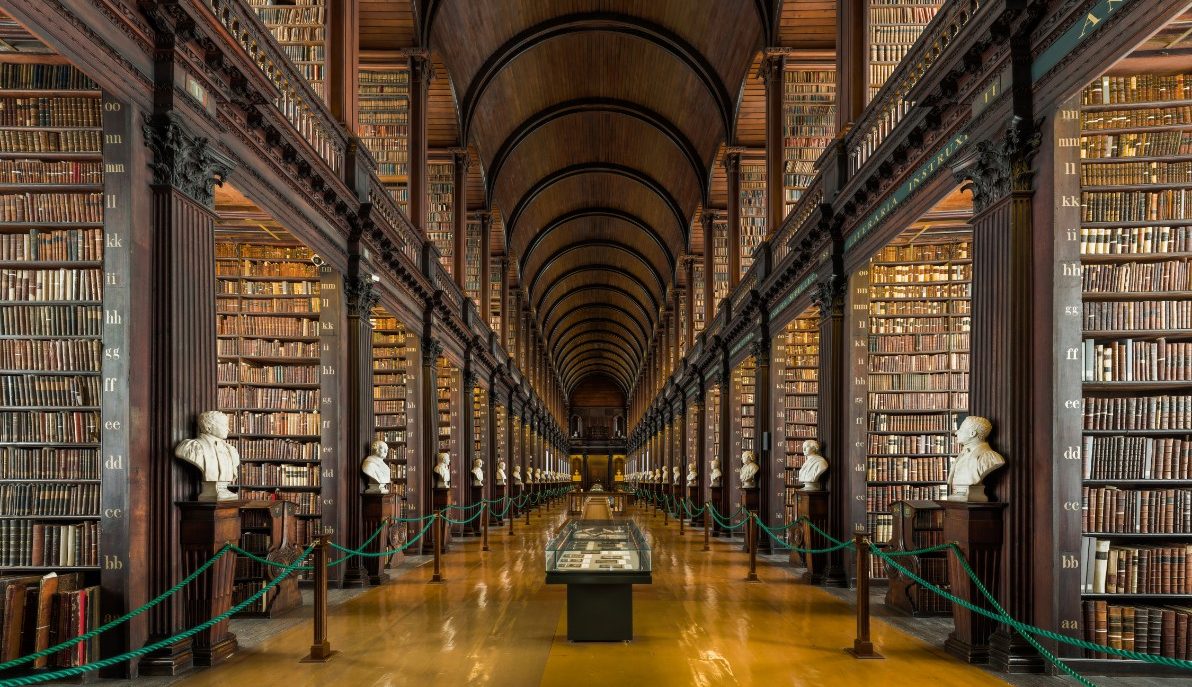

This also means that Penn expects more in terms of time and school-specific knowledge. Furda was one of the first college admissions leaders to set up a blog, and he has continued to use it vigorously. The current iteration of Furda’s admission blog is a full-on multi-page website that bears the name Page 217, a title taken from a well-known app essay prompt in which you had to write page 217 of your 300-page biography.

They don’t use that Page 217 prompt anymore, but it does reveal the philosophy of their approach— to think of a biography required you to think about the direction of yor own life, as well as to fit in something that indicated how Penn would fit in that biography. This Page 217 prompt demanded a sense of where your life was going and implied that you should have a sense of what Penn offers that would help you get to page 217. This is still the spirit of their essay prompts.

So there needs to be a sense of your past, as well as of your vision for your future, along with a good understanding of Penn, all rolled into one essay. But today, Furda has gone way past the creative riffing of the original Page 217 prompt. He has come up with a framework of things that he wants you to think about as you write an application essay.

This framework starts with his “5 I’s and 4 C’s.” Yep, nine things to look at right away, involving both introspection (the I’s) and research on Penn (the C’s.)

This is all about Demonstrated Interest, (also known lately by the more scientific-sounding “Interest Quotient”). Furda has found a way to roll D.I. into application essays. He wants it to be hard to reuse some boilerplate from other essays for the Penn app. Demonstrated Interest is increasingly important to elite schools, because they have to find a way to choose among the thousands of similar looking 3.9-4.3 GPA students with high SAT/ACT scores, two pages of activities, and who swear their devotion to . . . . fifteen different schools. Or more. If they offer you a seat, they want to have some certainty that you will accept the offer.

To meet their needs and to write a good Penn application for yourself, your essays have to show something about you personally, but also have to show your interest in Penn by dealing with Furda’s uniquely complex framework for writing. So let’s take a look at it:

The 5 I’s

A very cute idea, the 5 I’s are focused on you. Yes, in the country that has made defining yourself a lifelong project, Penn wants you to define yourself now. I list each of the I’s below, highlight the important buzzwords and phrases and discuss what the prompts are telegraphing in terms of content and focus. Notice this as you read the explanation by Penn (and my commentary): in their explanations, the good people at Penn are quite literally suggesting some areas–topics or subtopics–that an essay could focus on. But before I look at the “I’s” individually, let’s look at the actual essay prompt that the “5 I’s” address:

University of Pennsylvania Supplemental Essay for 2018-2019:

How will you explore your intellectual and academic interests at the University of Pennsylvania? Please answer this question given the specific undergraduate school to which you are applying (College of Arts and Sciences, School of Nursing, The Wharton School, or Penn Engineering). The essay should be between 400-650 words.

Basically, the 5 I’s are the focus of the first sentence in this Keeping that prompt in mind, let’s take the 5 I’s one at a time; here they are, with Penn’s explanation, followed by my commentary and analysis; the bold font is mine, to identify key phrases and words:

Identity–To figure out this piece, you must ask yourself who you are as an individual. How do you see yourself and how do you think that others see you? How do you drill into–essentially, unpack–the definition you create for yourself? Forget putting a name to a college now–don’t say I have to get into Penn or any other school. That comes later. Think about who you are without connecting yourself to anything external, such as brands, people, grades, etc. Think about who you are at your core.

The explanation on this one is not super helpful. How can you know yourself without connecting to anything external? Of course, their point is that they don’t want you listing accomplishments, etc, but we all define who we are in a relative way by comparison to who and what is around us. My suggestion: shrug and return to this one after doing some work on the other I’s, below. So let’s do that.

Intellect–How Do You Think and Approach the Acquisition of Knowledge? The explanation here is a bit more helpful. Again, I highlight the key phrases:

Part of your identity is your intellect. How do you think and how do you take in information? We want to know about your mind. Pretty simple, right? As educators, we know that all students have a unique intellect with different strengths and learning styles. Recognize that your intellect comes into play in a range of activities, not only while you are in class or doing homework. The problem solving skills that you utilize during club meeting, your perseverance during track practice, and the public speaking ability you employ while running for leadership positions are all positive manifestations of an intellect that is alive and growing.

This prompt seems to suggest that one of the more hackneyed topics, student government, could actually work here, but I think something else is better, as the typical high school leadership thing is now just a class, rather than being something you ran for and won. Something like taking the lead in the robotics club as you redesign your submersible, troubleshooting the design through reading in theory while tweaking various paremeters, persevering as it sinks, malfunctions and swims in circles, and almost drowns a teammate in the pool with it, and then, after an all-nighter of hands on problem-solving, fixing a leak and tracking down an electrical short while improvising with a butter knife due to the fact that a teammate left all the philips head screwdrivers at the airport, and delivering your personal Saint Crispin’s Day Speech, at three a.m., as your team was ready to quit, then winning that Navy competition (or placing third, or even competing at all–hey, it was a miracle your ‘bot even made it into the pool) –that might be better essay. subject.

My message here is to look at everything you are doing for inspiraiton. It is not just okay to have a bit of overlap with your activities; if an activity is your passion, you actually need more space to talk about it. Just don’t make your essay a pure recap or list of actities and accomplisments. The example above is probably for a person with engineering in mind, of course.

Note that my summary of a particularly interesting activity, focused on an example, shows a range of things, with hands-on learning, problem-solving skills and leadership. Also notice that if you put it in first person, you would have an essay subtopic of about 185 words, leaving hundreds more available in this Penn essay.

Ideas–We want to know what you think about and why. When you have time to hang out, what are your ideas? What do you think about big issues like global warming? What do you think about local issues right here in your backyard? What are your ideas and what has informed those ideas? Ideas are what make college communities really interesting. When diverse students with unique intellectual paths share their thoughts with one another, it results in a great synergy. Students who work together, crossing traditional academic boundaries, have the potential to make waves in their community and world. So yes, your ideas, even if at this point they don’t seem realistic, can help you get into college. We are interested in the intellectual innovation you will bring to campus. We are interested in your spark.

So this is great: what a wide field of ideas! But my warning is to beware of the “Beauty Queen” essay, or the “Dude, have you every thought that the entire universe might be, like, an atom on the fingernail of a God” ramble. Read my link on the Beauty Queen and click around to read more of my posts on the problem essay–the subjects may have changed, but the basic ideas are the same. Warning: be sure that these big ideas are things you have connected with at a deeper level than Pinto, in my link above. The best ideas to discuss are ones that you have not just thought about in your spare time but that you have also done something about in your spare time, even if that just means chasing down more information on the idea. Assuming you have spare time, of course.

Interests: What do you like to do? What do you like to do when someone is not telling you to do it? What are your hobbies? This is one way that I think about interests: If you could pick up three books or three magazines, what would they be? Sometimes we need to pick books or magazines up because they feed into the courses that we are taking; other times it is a reflection of our natural acclimations* and interests. You can do the same exercise with films, or museums. When you walk into a museum, what is the first section that you go to? All these things are going to be interesting to you and they’re going to interesting to the community that you are looking to be part of in college. *(I think they meant to say inclinations here. Hey, it’s a blog, not a dictionary . . . I guess.)

Quite a few schools ask you to write about things you read, mentioning books more often than magazines. However, when you write about books, you may feel you have to fall back on the literary analysis or argument format that you were taught to use in your English class. This is more a first-person interest essay. There are ways to work in some level of analysis however, and I have posted advice and analysis on writing about books a number of times–have a look at this as an example: How to Write about Books. As always, the purpose in writing about books is to show what you are like, not to interpret what the river means in Huckelberry Finn. So this is a bit like that old-fashioned art of choosing which books to put on the bookshelf in your living room, so that they make a statement about you.

Haven’t had time to do anything but the “required reading? No time to start like the present, and since you are likely a super-connected post-millenial person, why limit yourself to paper? There is such a thing as an online magazine or journal. In the areas of literature, the arts and politics, you could take a look as sites like n + 1 magazine (comes in printed form as well), or for a more purely literary slant, Tin House. There are, of course, still the old-school but excellent mags on culture, politics and art from the days of paper, like The New Yorker, Harpers and The Atlantic, or for more political slant, the liberal Mother Jones, which also does quite a bit of investigative journalism, or The National Review for you young (but traditional) Republicans out there. Breitbart–give it a pass for this one, unless you are showing how you like to see what the lunatic fringe is thinking. A couple of hourse of reading and looking around while taking notes can set your foundation as a budding intellectual–no time to start on that like the present.

As for visiting museums, well let’s just say that this really telegraphs more about the person who wrote the prompt than anything else, and conveys the assumption that you live in an urban core with parents who encourage museum-going, or that you are in an upper-middle class suburb, with access to a city, and ditto the parents. Of course if you do like to visit museums–I have clients who are artists, or into paleontology, or like to visit the Tech Museum, etc, etc–go for it.

Next (and last up for this post):

Inspiration-–What really motivates and inspires you? We can sit down for forty-five minutes and you might not be sure how you want to answer this question or you might be thinking too hard about it. But then, there is this point in the conversation where I ask you something and your eyes light up and your arms start to move about. You are inspired; something really moves you. Tap into this power source and build on it.

When in doubt, look at your responses to the I’s above. If you have not talked about ideas and activities that inspire you above, then you need a do-over on those. And any discussion of your passion needs to have some concrete stuff that you do to show it.

As for who you are at the core, same thing: your passions should tell you that, as should all the other “I’s.”. But some broad questions may help–are you a thinker? A doer? Political or not? Do you analyze and break down or does your mind leap to an answer? Do you learn through the physical world or navigate the e-realm more?

Come back soon; I will post again about Penn, this time looking at The Four C’s, which means researching Penn in more detail

Demonstrated Interest, indeed.

You can follow my blog to see when I post on this again, or just contact me for help with college essays. My editing and essay development is the best in the business.